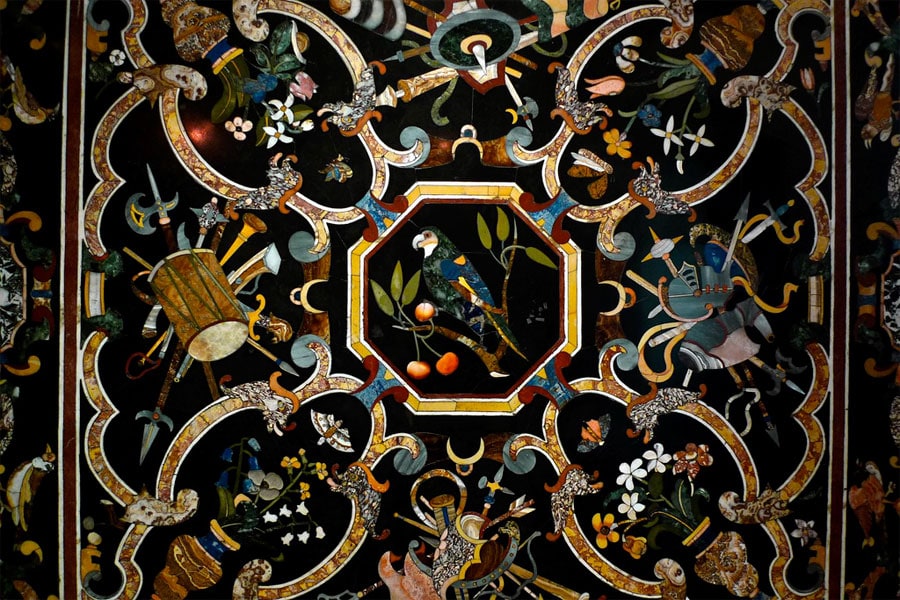

Detail of an important Exhibition Florentine Renaissance Revival Pietre Dure and Carved Giltwood Centre Table, The pietre dure by Gaetano Bianchini, The Carved Giltwood Base by Angiolo Barbetti. Exhibited at the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle.© Adrian Alan Ltd

Rome in the early Sixteenth Century was the catalysing centre of High Renaissance culture. It was here that the cult of the Antique, and the excitement of archaeological discovery was fostering a lasting passion for the marbles and rare stones that had adorned Imperial Rome in the days of her splendour. In Rome there was also a tradition of skilled marble working that had survived throughout the Middle Ages and made possible the revival of ingenious techniques such as ‘opus sectile’.

Tigress attacking a calf, marble opus sectile (325–350 AD) from the Basilica of Junius Bassus on the Esquiline Hill, Rome

This was a composition of irregular sections of coloured stone, used since the days of the Roman Empire, mainly for the covering of pavements and walls.

The Renaissance brought about a revival and refining of this technique and saw its adoption for display furniture for the homes of rich and cultivated patrons, in a form know as ‘intarsia’.

Detail of an intarsia panel from the floor of Sienna Cathederal depicting Siena’s emblem: the she-wolf nursing Senius and Aschius (the sons of Remus, who supposedly ran away from Rome and from their cruel uncle Romulus to then found Siena). The intarsia was undertaked from circa 1373 and was renewed in 1864/65. The original mosaic can be seen at the OPA museum.

The Medici family were amongst the keenest admirers of Roman ‘intarsia’ work, and it is clear that it played an important part in the birth of ‘Florentine mosaic’, later to be known as ‘Pietre Dure’, which was far more complex, and involved the creation of motifs and pictures, not just the geometrical shapes of the earlier ‘intarsias’.

In 1588 Grand Duke Ferdinando I founded in Florence the ‘Galleria de’ Lavori in Pietre Dure’, a hardstone workshop combining all the Grand Ducal workshops. He hired local craftsmen and trained them to restore ancient carved-stone objects as well as create original works in ‘pietre dure’. These artists soon perfected the art of making pictures with thin pieces of brightly coloured semi-precious stones. By the end of the century, Florence was to hold an international supremacy in the highly specialised field of ‘pietre dure’ that was to last for nearly three Centuries.

During the 1600’s the Galleria’s work was mainly restricted to Florence, concentrating on the decorations of the Medici family’s chapel in the church of San Lorenzo, begun in 1605, and the Tribune in the Uffizi, intended to be a showcase for the finest pieces in the Medici collections. But by the 1700’s, when ‘pietre dure’ became increasingly fashionable, artists trained in the workshop travelled all over Europe to work for other noble or royal households.

Erected between 1604 and 1640 by the architect Matteo Nigetti following the designs of Giovanni de Medici. The inlay of the semi-precious stones, executed by highly skilled workers from the Opificio delle Pietre dure took several centuries to complete. – Erected between 1604 and 1640 by the architect Matteo Nigetti following the designs of Giovanni de Medici. The inlay of the semi-precious stones, executed by highly skilled workers from the Opificio delle Pietre dure took several centuries to complete.

The Tribune, Uffizi Museum

The Tribune was realized between 1581 and 1583 by architect Bernardo Buontalenti “to keep jewels and embellishments of the Grand Duke”, Francesco I de’ Medici.

Brilliantly coloured flowers, fruits, and birds on a ground of black paragone were consistently the favourite compositions for ‘pietre dure’ works. In these designs the memory of Ligozzi’s (1547 – 1626) naturalism coexists with extreme stylisation. The plant theme was also to be continued in the festoons of bronze foliage and ‘pietre dure’ fruits, for which the Galleria even created a new job of ‘fruttista’.

Detail of a table top in the Museum Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence

The last member of the Medici family died in 1737 and the dynasty was replaced by the Austrian Hapsburg-Lorraine family. The Lorraine period, continued to foster the success of the laboratory, particularly in pictorial compositions. Most notable being the pictures in semi-precious stones to the design and models drawn by the painter Giuseppe Zocchi delivered to the Court of Vienna.

Giuseppe Zocchi 1776 – 1780, The Liberal Arts, Paitning and Sculpture

A Florentine Ebonised and Parcel-Gilt Pietre Dure and Specimen Marble Cabinet-on-Stand, Castagnoli, Florence. © Adrian Alan Ltd

Inscribed ‘Castagnoli fece Fierenze’, this fine pietre dure and hardstone inlayed cabinet would have been made by one of the thriving 19th century Tuscan workshops for an enlightened connoisseur on the Grand Tour.

The central niche opens to a concealed sanctum sanctorum containing a figure of Mercury after Gimabologna. One of the most recognisable Renaissance sculptures, it was created around 1564 intended as part of a fountain for the Medici in the Villa Medici in Rome. Known as the messenger of the Gods, Mercury was venerated in Roman times as the god of commerce, profit, and wealth, a very suitable Medicean trope.

The end of the Tuscan Grand Duchy in 1859 was to see the end of the Gallerias dominance since it had always been so closely linked to the Court.

The House of Savoy almost completely ignored the manufactory, preferring to obtain their furnishings and gifts from private Florentine workshops, most notably that of Enrico Bosi.

The 1870’s did see commissions to the Galleria from other monarchs such as Ludwig II of Bavaria and Alexander II of Russia, for pieces in the grand tradition of the past, and such productions maintained earlier levels of quality and taste.

The 1870’s did see commissions to the Galleria from other monarchs such as Ludwig II of Bavaria and Alexander II of Russia, for pieces in the grand tradition of the past, and such productions maintained earlier levels of quality and taste.