Meissen

The ‘Diana and Actaeon’ Vase – A Large Meissen Porcelain Two Handled Vase, Painted By Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872)

POA

The ‘Diana and Actaeon’ Vase A Large Meissen Porcelain Two Handled Vase, Painted By Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872). Model Number G.103. The...

Размеры

Высота: 100 см (40 дюймов)Width: 58 cm (23 in)

Depth: 44 cm (18 in)

Описание

The ‘Diana and Actaeon’ Vase

A Large Meissen Porcelain Two Handled Vase, Painted By Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872). Model Number G.103.

The body finely painted with a continuous mythological scene of ‘Diana and Actaeon’ above flowerhead and acanthus leave gilt-embossed decoration on a claret ground. The neck with a continuous scene of cupid’s chariot and Diana enchanting the sleeping Actaeon. The socle painted with deer and hounds. The upright scroll handles parcel-gilt and with mask terminals.

Blue crossed swords mark. Incised ‘G.103’ / ‘8’.

Germany, Circa 1865.

Recorded by Meissen with the title ‘Prunkvase mit maskarons’ (‘Magnificent vase with mascarons’), the vase is distinguished as a masterpiece by the breathtaking quality and detail of the painting.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld was a celebrated German artist who worked as an illustrator and painter, who worked to revive fresco painting and also designed monumental architectural artworks, including stained glass windows. His style is characterised by a precise linearity, clear bright colours, and a multiplicity of symbolic detail and was inspired by early Renaissance art and the works of Albrecht Dürer.

Portrait of Von Carolsfeld as a young man (1820), by Friedrich von Olivier, Albertinum.

Source Wikipedia, Public Domain.

His character and style are clear in the decoration of this vase. The shape of the vase and its mask handles are Renaissance inspired, whilst the antecedent for the subject are paintings by Titian of ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and ‘The Death of Actaeon’.

‘Titian’s ‘Diana and Actaeon’, 1556–1559.

(National Gallery, London.Wikipedia, Public Domain)

The tale of the hunter Actaeon, who beheld Diana bathing and was punished by being transformed into a stag and destroyed by his own hounds, can be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Diana, or in ancient Greek mythology Artemis, is the goddess of the hunt. She is bathing with her nymphs at a spring when the mere mortal Actaeon unwittingly stumbles upon the scene. In the confusion of the surprise Diana splashes him with water, and he is transformed into a stag and robbed of his voice. Fleeing in fear he is tracked and killed by his own hounds, who fail to recognise him.

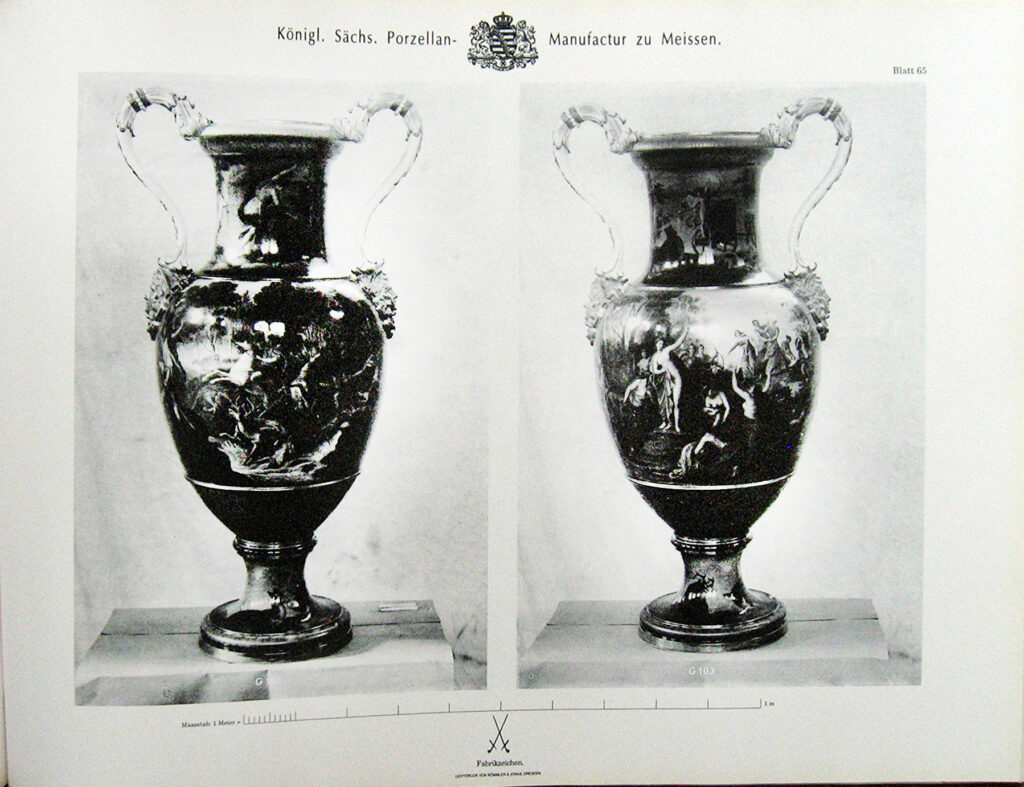

‘Diana and Actaeon’ Vase in a period Meissen Catalogue (courtesy Meissen Porcelain Museum).

There are two other known examples of the ‘Diana and Actaeon’ vase. One is in the Meissen Porcelain Museum and another appeared on the market in 2021. Between these there are minor differences, such as to the painting of the neck and to the patterning of the gilt-embossed decoration on the claret ground.

Another example of this vase in the Meissen Porcelain Museum.

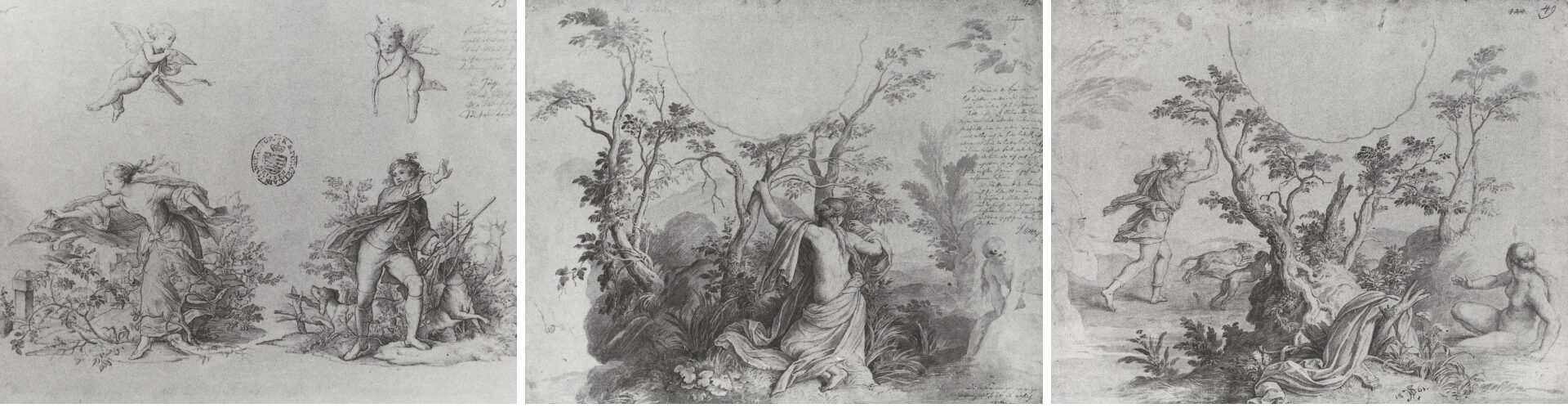

The Meissen Porcelain Museum holds three sketches by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, dated 1861, exploring the subject of Diana and Actaeon.

Drawings by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld showing Diana and Acteaeon. (courtesy Meissen Porcelain Museum)

In the Booth-Clibborn Collection there is a drawing by Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld dated 22 October 1865 which is the exact design of Diana bathing to the front of this vase.

Diana and Actaeon, 1865 (pen and brown ink with brush and wash over graphite) by Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Julius (1794-1872); Booth-Clibborn Collection. © Bridgeman Images

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld was one of a number of academy artists which were brought to work at Meissen as consultants and designers to give the manufactory a more artistically orientated direction. By 1853 Schnorr was advising the Meissen Manufactory on artistic issues having already designed the Bacchus decoration for a vase shown by Meissen at the 1851 Crystal Palace in London. He is also credited with designing the decoration for a pair of vases representing the seasons for the London 1862 International Exhibition and a richly painted porcelain table for the Paris 1867 Exposition universelle. Schnorr received his earliest instruction from his father, Hans Veit Schnorr, a draftsman, engraver, and painter. He studied at the Vienna Academy from 1811 and, from 1817 to 1826, in Rome, where he painted the spectacular frescos in the Ariosto Room at the Casino Massimi. In 1827 he moved to Munich in the service of Ludwig I of Bavaria and began the Nibelungen frescoes at the Residenz. In 1846 he became professor at the academy and director of the picture gallery in Dresden.

Дата

Circa 1865

Происхождение

Germany

Средний

Фарфор

Подпись

Blue crossed swords mark. Incised ‘G.103’ / ‘8’.

Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, painted by Nicolas de Largillierre (1656–1746) circa 1714–15, oil on canvas (Wikipedia: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri).

The production of Meissen porcelain began in 1710 at the manufactory at Meissen, near Dresden, under the patronage of Augustus the Strong of Saxony (1670-1733). In the 17th century Europeans were so in thrall of Chinese porcelain, which was ‘high fired’ and so prized for its white and translucent quality, that they called it “White Gold”. Meissen porcelain is world famous, because it was at Meissen that the recipe for pure white biscuit porcelain was first discovered in Europe. The discovery attracted artists and modellers to work at Meissen and its production was so successful that in 1720, its signature logo of crossed swords was established as one of the oldest trademarks in existence.

The discovery of the recipe for porcelain was made when the alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger, who had unsuccessfully been trying to make gold for Augustus the Strong, took on the work of the scientist Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus and discovered the final piece of the puzzle needed to make porcelain: that white kaolin must be used in place of red clay.

Augustus the Strong moved von Tschirnhaus’ laboratory to the Albrechtsburg Castle in Meissen and on 6 June 1710 established the ‘Royal Polish and Electoral Saxon Porcelain Manufactory’. The intention was that the secret would remain safe within the castle walls, but soon the recipe was being copied throughout Europe. To signify the exceptional quality of Meissen porcelain the Crossed Swords mark, taken from the arms of the Electorate of Saxony, was introduced.

The Japanese Palace, Dresden, Circa 1722-27.

By 1720 Augustus the Strong had built his ‘Japanese Palace’ to display his vast collection of Far Eastern and Meissen porcelain. The centrepiece, planned from 1730 onwards was a porcelain menagerie which was intended to house nearly 600 life-size animals and birds which had been ordered from Meissen. In the event the complexity of making lifesize three-dimensional animals led to technical delays and Augustus the Strong died in 1733 before all could be completed. The modeller for animal figures for the ‘Japanese Palace’ was Johann Joachim Kändler (1706–1775), a German sculptor whose works produced at Meissen would come to substantially change the porcelain industry. Kändler produced other animal sculpture, including one of Clara the rhinoceros, but following the death of Augustus the Strong and as his successor Augustus III had no interest in porcelain, control of the factory was given to the more commercially minded Count Heinrich von Brühl, and Meissen turned away from animal sculpture towards table services. Kändler created for von Brühl, ‘The Swan Service’ of tableware which is modelled in relief with swans and considered a masterpiece of porcelain art. It heralded a move to small decorative figures for which Kändler is best remembered. These figures which took inspiration from court life and were inspired by the Commedia dell’arte, extended to pastoral and mythological subjects, harlequins and the famous ‘Monkey Band’, and were imbued with the playful imagery of the rococo style and came to number over a thousand different items.

Meissen remained the dominant European porcelain factory until 1756 when Frederick the Great of Prussia attacked Saxony, launching the Seven Years War (1756-63). Dresden was occupied and the ensuing disruption at Meissen allowed other factories, notably Sèvres in France, to invade markets and create fashions. Kändler’s lifetime encompassed the three main 18th century styles: baroque, rococo and neoclassicism, and his death in 1775 marked the end of the great period at Meissen. Thereafter, Meissen adapted to the neoclassical style but never rivalled Sèvres in the elegance of its designs.

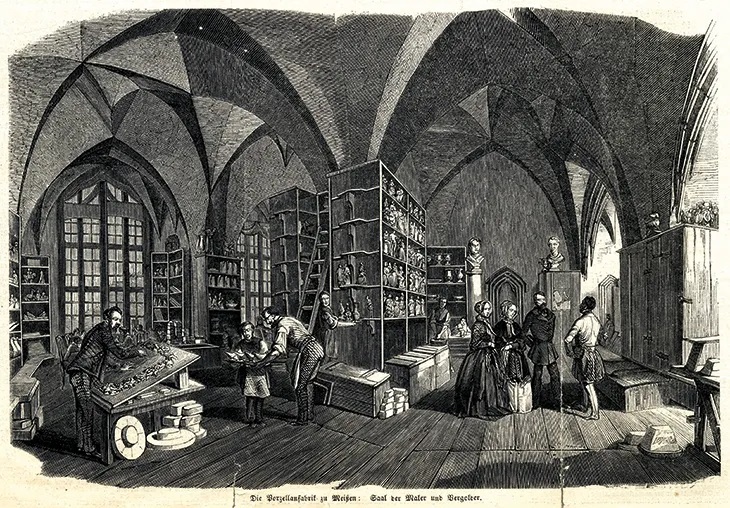

Illustration of the Meissen modelling studio in Albrechtsburg Castle, Meissen, just before the move to a dedicated factory (Source: Apollo Magazine © Schlösserland Sachsen).

In the late 18th and early 19th century Meissen faced tariffs and import bans from Britain, France and Russia who sought to protect their own porcelain industries. In 1810 work at Albrechtsburg Castle came to a halt and the first centenary of Meissen is overshadowed by fraught circumstances until Heinrich Gottlob Kühn (1788-1870) assumes control in 1814 and overseas numerous technical advances. By the middle of the 19th century, under Kühn’s management and Ernst August Leuteritz’s leadership of the design department, there began a transformation of Meissen’s fortunes with a new factory in the Triebisch Valley area of Meissen opening in 1861.

Meissen porcelain at the 1862 International Exhibition in London. (J. B. Waring, Masterpieces of Industrial Art & Sculpture at the International Exhibition, Londonm 1862).

Stereoscope image of Meissen’s Display at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

Considerable commercial success followed at the 1862 London and 1867 Paris International Exhibitions. By 1871, sales revenues amounted to 370,000 thalers, compared to the Royal Porcelain Manufactory in Berlin which earned 160,000 thalers. During the second half of the 19th century there was a great revival of Kändler rococo figurines which were reissued and a “Second Rococo” of latticework and flower-encrusted vases. In 1884 and 1885 Meissen fulfilled an important commission of flower decorated chandeliers, mirror frames, tables and other ornament to the Bavarian ‘fairytale’ king, Ludwig II. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, Meissen presented over 1000 items in this historicist style as well as tentative examples of Art Nouveau.

At the inception of Meissen porcelain, the alchemist Böttger had made an unlikely promise to Augustus the Strong, but in time it became a reality: ‘that in the future, given the right design and production, white porcelain of this kind…shall be able to surpass Asian porcelain by far, not only in beauty and quality, but also in variety of shapes and large pieces, some even solid, such as statues, columns, service and so on’ (See Samuel Wittwer, The Gallery of Meissen Animals, Munich, 2006, p.322).

Literature:

H. Morley-Fletcher, Meissen, London, 1971.

Dr. K. Berling, Meissen china; an illustrated history, Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Meissen, 1972.

N. Harris, Porcelain Figurines, London, 1978.

H. Jedding, , Meissener Porzellan des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, 1800-1933, 1981.

H. Sonntag, Meissen in Meissen: Europe’s first porcelain, Leipzig, 2003.

H. Morley-Fletcher, Meissen, London, 1971.

Dr. K. Berling, Meissen china; an illustrated history, Staatliche Porzellan-Manufaktur Meissen, 1972.

H. Jedding, , Meissener Porzellan des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, 1800-1933, 1981.

Thomas and Sabine Bergmann, Meissener Künstler-Figuren. Band I: Modellnummern A 100 – Z 300, 2010, Catalogue Number 2092.

Печать

Печать