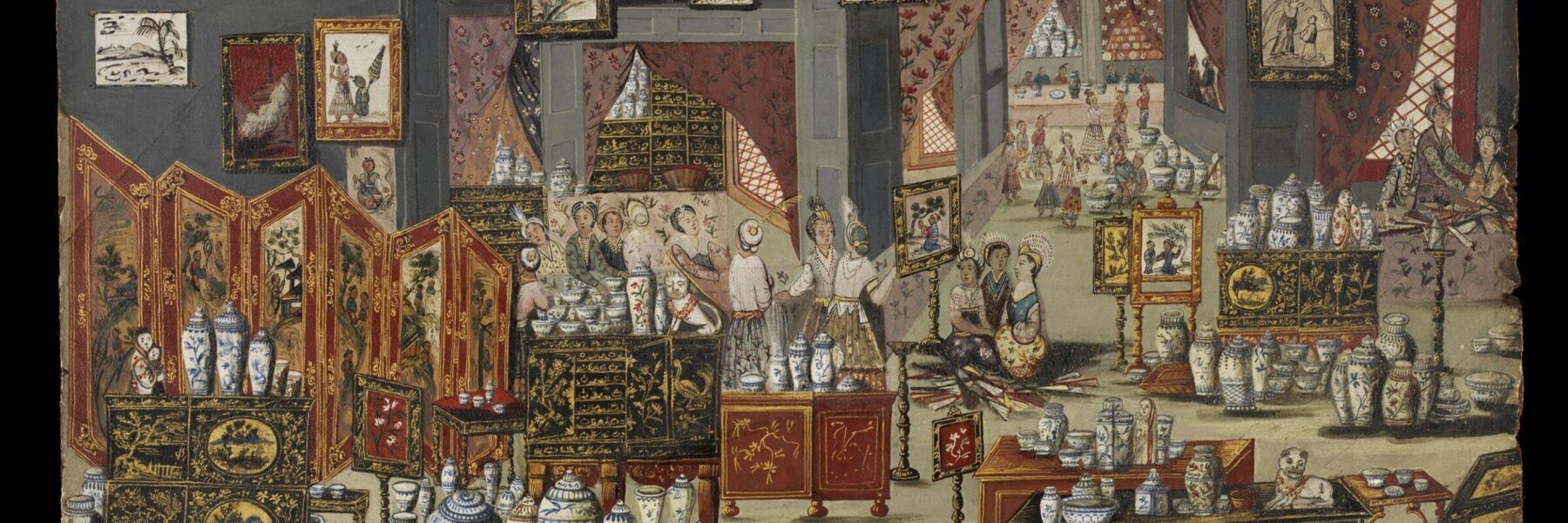

The origins of Chinoiserie lie in early trade of ‘true’ hard paste porcelain, the secret of which was only known in China. Asian arts including porcelains, lacquer wares, jades and silks were transported to Europe first by Indian and Arab traders and later by the Dutch and English East India companies. Henry VIII (1491-1547) owned Chinese porcelain which was lost or sold during the English Civil War. Queen Mary (1662-1694) collected Chinese blue-and-white and blanc de Chine porcelain and her apartments at Hampton Court palace had chinoiserie interiors lined with panels of Eastern lacquer, the porcelain atop wall brackets above mantelpieces and doors. The Dutch imported considerable quantities of Chinese porcelain in the 17th century but only the very wealthiest collectors could afford the early imports. Impressed by the quality and detail of Chinese workmanship, Dutch potters in the city of Delft began to produce tin glazed earthenware, a type of faience blue and white pottery inspired by Chinese originals.

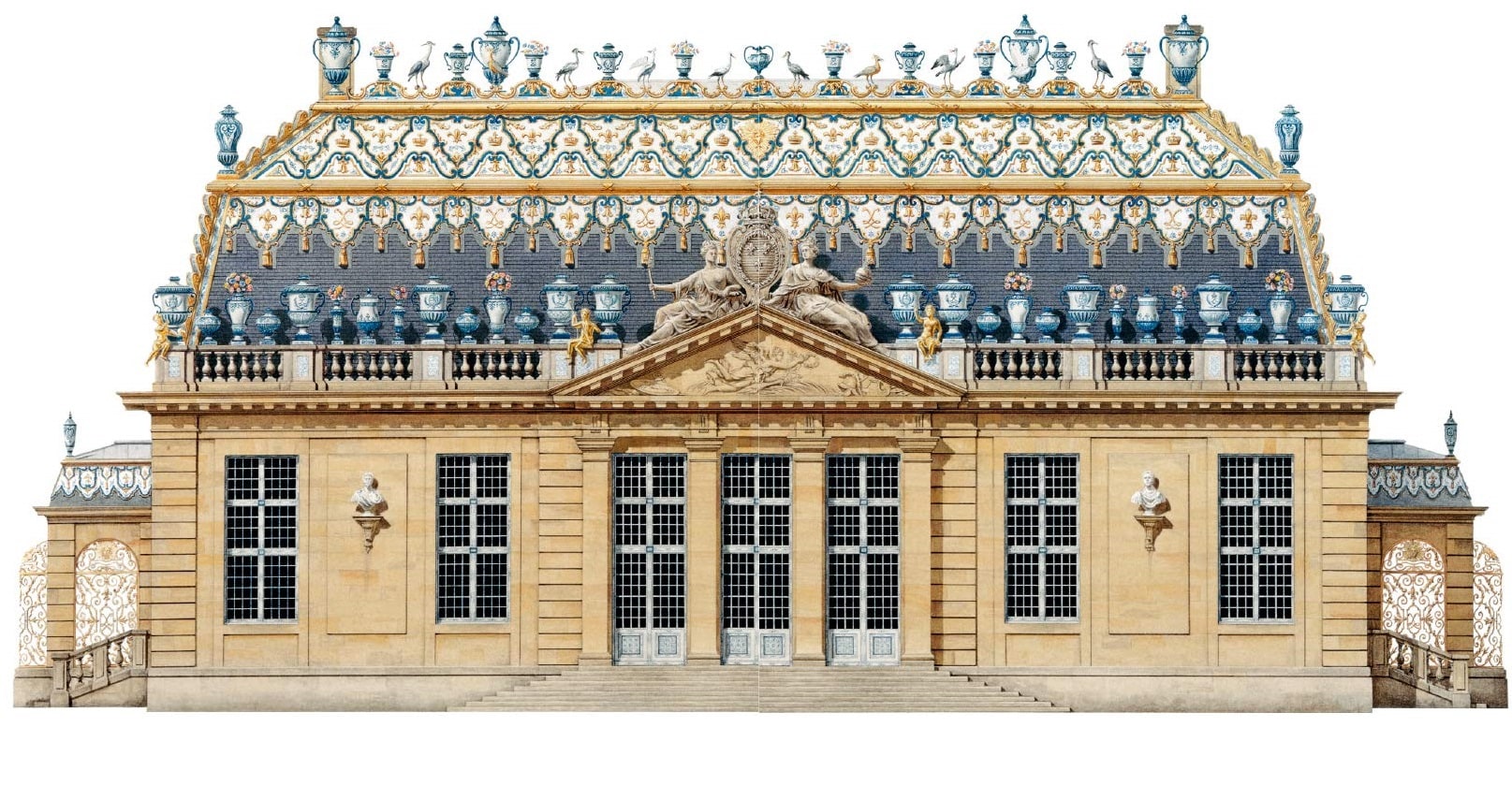

An artist’s impression of Louis XIV’s Trianon de Porcelaine built in the grounds of the Palace of Versailles in 1670 and considered to be the first Chinoiserie building in Europe. It was an attempt to emulate accounts received of the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing. The Chinese style pottery vases arranged along the ridge and the roof tiles were made of faience produced by potteries in the Netherlands (Delftware) and France. The interior decoration – ceramic tiles, woodwork, stucco, other surfaces, and furniture – were all painted white and blue, ‘à la chinoise’

The importation of enormous quantities of goods from the Far East to France by the Compagnie des Indes Orientales stimulated increased interest in China at the end of the 17th Century. The enthusiasm was further heightened by Louis XIV’s glamorous reception for the ambassadors of Siam in 1664 and the publication in the same year in the Mercure Galant of a long description of the travels of father Couplet to China. When in 1682 Louis XIV moved the French court from Paris to Versailles, and set-about transforming the one-time hunting lodge into palace, chinoiserie contributed to the otherworldly opulence. The implicit meaning was that the bourbon monarchy was at the centre of the world.

Woven at the French Royal Beauvais Tapestry Manufactory between 1685 and 1690 The Audience of the Emperor is one of a series of tapestries depicting scenes from the life of the Chinese Emperor, believed to be Shunzhi (reigned 1644 – 1661) and KangXi (reigned 1661 – 1721).

The magnificent Banqueting Room at the Royal Pavilion, showing decorative wall canvases depicting Chinese domestic scenes, from John Nash’s Views of the Royal Pavilion (1826)

A formative example of Western interest in Chinese art and architecture is the Great Pagoda at Kew which was completed 1762 as a gift for Princess Augusta, the founder of the Gardens. Princess Augusta with Princess Elizabeth greatly influenced their brother, George IV’s Chinoiserie interiors at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton. The architect John Nash, responsible for the Pavilion’s distinctive Indian and Gothic exterior, employed the designers Frederick Crace and Robert Jones for the interiors. Reflecting George’s love of Asian art and design the pavilion abounds with Chinese wallpapers, furniture and objects as well as large quantities of bamboo and lacquer furniture. Chinoiserie works of art often have complex origins. For example, a French secretaire might be adorned with Japanese lacquer panels or an English table decorated with Chinese motifs.

A 1763 watercolour drawing by William Marlow of the magnificent Chinese Pagoda of Kew Gardens which was designed in 1757 by William Chambers.

A view of the Chinese Drawing Room at Carlton House illustrated by Thomas Sheraton his Cabinet Maker’s and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book, 1793. It was the earliest expression of King George IV’s fascination as Prince Regent with the Far East. The combination of Chinese and Japanese works of art and bespoke furniture was the result of a collaboration between the architect Henry Holland and the French designer Dominic Daguerre.

The Yellow Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace contains many objects from the Chinoiserie decorative scheme by Frederick Crace for the Royal Pavilion in Brighton.

The Chinesisches Haus is a garden pavilion in Sanssouci Park in Potsdam commissioned by Frederick the Great and completed in 1764. Inspired by Chinese architecture and attended by sculptural Chinese figures, the chinoiserie interior has a rococo flavour which is designed to exude the relaxed lifestyle of an ideal world that was supposedly China. Note the wall brackets for Chinese porcelain vases, wall murals of imagined Chinese figures, and sculptural elements.

It became fashionable from the mid-18th century onwards in England devote a room to the Chinoiserie style. At Claydon House in Buckinghamshire the walls are painted in Chinese powder blue coupled with remarkable stucco rococo Pagoda plasterwork and Chinese export furniture. Chinese painting workshops responded to the fashion by producing sets of paintings on paper which could be painted on walls and this gave rise to the fashion for Chinese wallpaper such as at Nostell priory were Thomas Chippendale not only supplied the furniture but sourced the Chinese wallpaper featuring exotic birds in flowering trees.

Claydon House. Image courtesy of Andreas von Einsiedel

Chippendale also supplied spectacular Chinese wallpaper to Harewood House in 1769. It is a continuous landscape of traditional Chinese rural working life depicted in vibrant colours and a rare survival for it was cut from the walls sometime in the early 19th century and stored rolled up in linen in an outbuilding for nearly 200 years until it was rehung in Edwin Lascelles’ bedroom in in 1988.

Empress Eugénie, wife of Napoleon III, created the Chinese Museum at the château de Fontainebleau in 1863. The Chinoiserie interiors are designed to complement the collection of Chinese ceramics, lacquer, furniture and works of art, of which a considerable quantity was removed following the ransacking of the Old Summer Palace when British and French troops invaded Beijing. The Musée Chinois at Fontainebleau helped reawaken the vogue for Chinoiserie.

Chinoiserie remained fashionable into the nineteenth century, apart from a temporary decline in popularity in Britain following the First Opium War of 1839 – 42 between Britain and China. The fashion for the ‘le style japonais et chinois’ swept Paris again in the mid-19th century and was inspired by Empress Eugénie’s Musée chinois at the Château de Fontainebleau and the opening of trade with Japan.

Today Chinoiserie is well understood as an idyllic representation of Chinese and East Asian culture and continues to provide a rich source of inspiration for interior decoration and fashion.

Chinoiserie with its whimsical and colorful approach remains a an influential deign source today. Amazonia-designed wallpaper. Image via de Gournay.