风格灵感

美好年代

A swan song to the beautiful age

L’escalier de l’Opéra in 1877 By Louis Béroud (1852–1930 (©Musée Carnavalet)

The Belle Époque was characterised by prosperity and technological innovation which ignited a flourishing of the arts. Referencing the period from the 1870s to the outbreak of World War I in 1914, a time of relative political stability, the French expression ‘La Belle Époque’ was coined in retrospect and is imbued with nostalgia for a better time before the horrors of world war.

As the clock counted down to 1900 and the dawn of a new century, an irrepressible sense of optimism was gaining momentum. This optimism was born from the progress brought by daily new wonders of science and technology. The city slums were being swept away by boulevards, the dim streets emblazoned by electric light, the telephone had broken down borders and a new middle-class had emerged emancipated, and for the first time in history unencumbered by the labour of mere survival, but instead hungry for comfort, art and pleasure, in all its myriad forms.

‘Le Boulevard St. Denis, Paris’ – Jean Béraud 1875

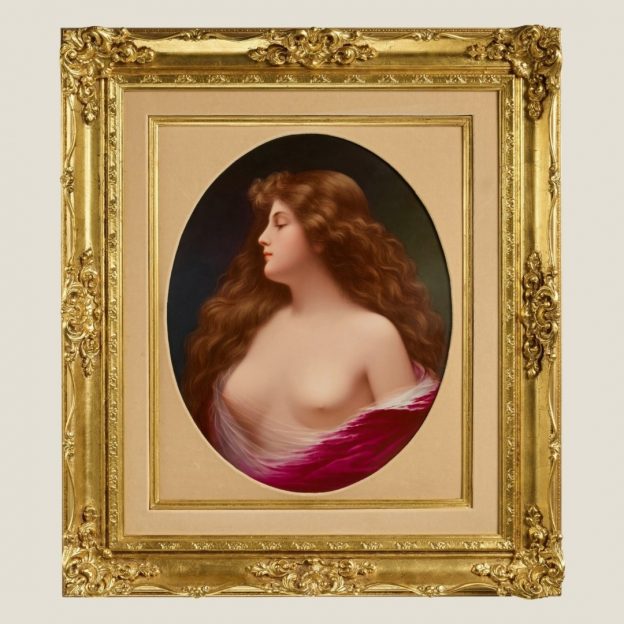

Today, in art history when we look back at the dawn of the twentieth century, we are taught about avant-garde artists and movements such as Symbolism, Fauvism and Expressionism. The artistic importance of the Belle Époque is often overlooked in favour of glamourising the undercurrent of rebellious and revolutionary art. The Belle Époque is dismissed as nothing more than an affectation of the bourgeoisie and is often negatively defined artistically for its decadence, opulence and frivolity. Too often there is a false assumption that art, from this period of nationalism and colonialism, must be nothing more than overstuffed, academic and official.

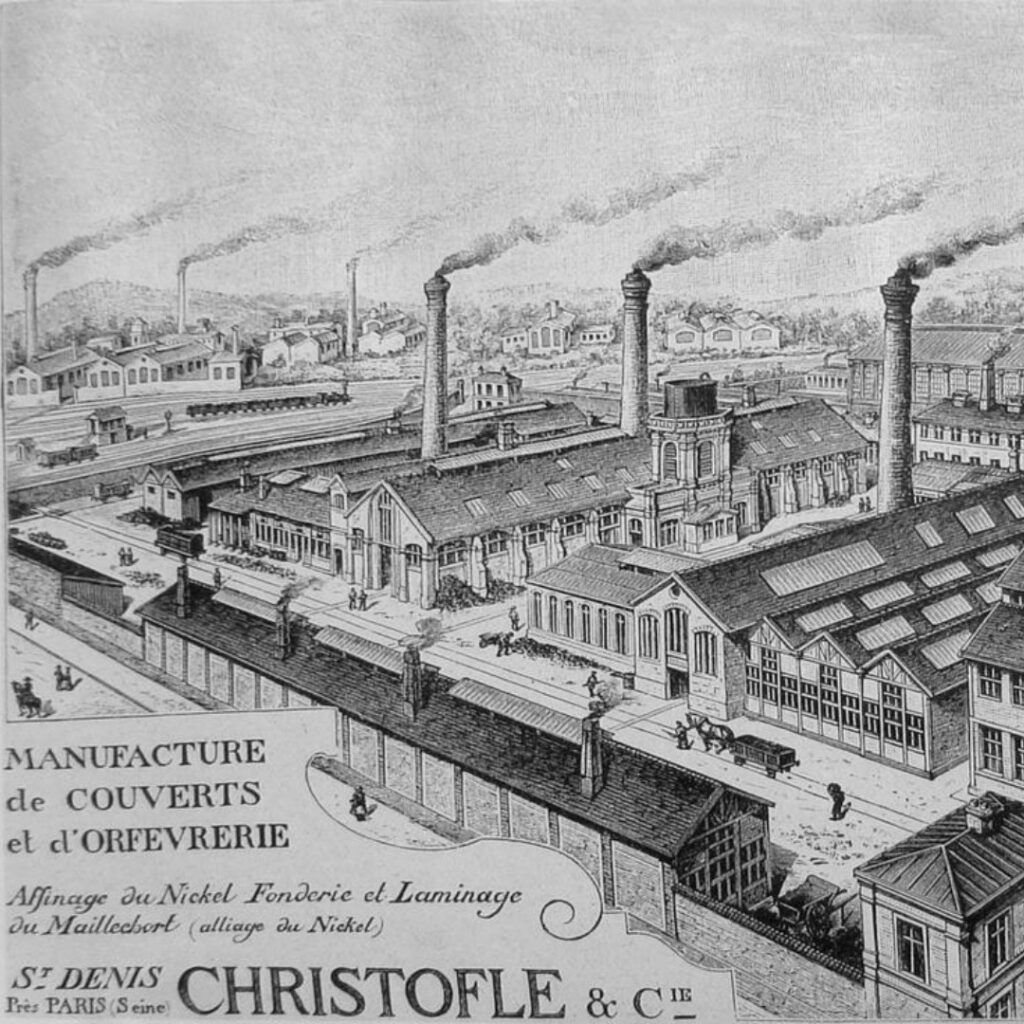

Such a simplification is a construct of today, and in reality, the Belle Époque stimulated artistic representation at all levels of society. There was the art of the establishment offset against revolutionary art, but central to the Belle Époque is the ‘art of industry’. Industrial art utilised new machinery, such as the power saw, and techniques, such as electroplating, to realise ambitious works of art, designed to show both the artistic accomplishments and technological superiority of the manufacturer. Pre-eminent art manufacturers such as the bronzier Barbedienne and the silversmith Elkington, who had prospered making tableware and ornaments for the middle classes, utilised the considerable resources at their disposal to produce a handful of unbelievably lavish objets d’art for display at the great exhibitions of the late nineteenth century.

The Christofle Factory, St. Denis, Paris

Detail of the ‘Japonisme’ top of a gueridon by the French silversmith Christofle dated 1885, which shows their expertise in ‘oriental’ enamel technique.

Technological advances had enabled a perfection of assembly of art objects of a quality hereto unimaginable. For example, the French silversmith Christofle, using their technological expertise, were successful in imitating the Japanese techniques of cloisonne enamel and mixed-metal bronze patination, previously the handmade output of Japanese craftsman working centuries old techniques.

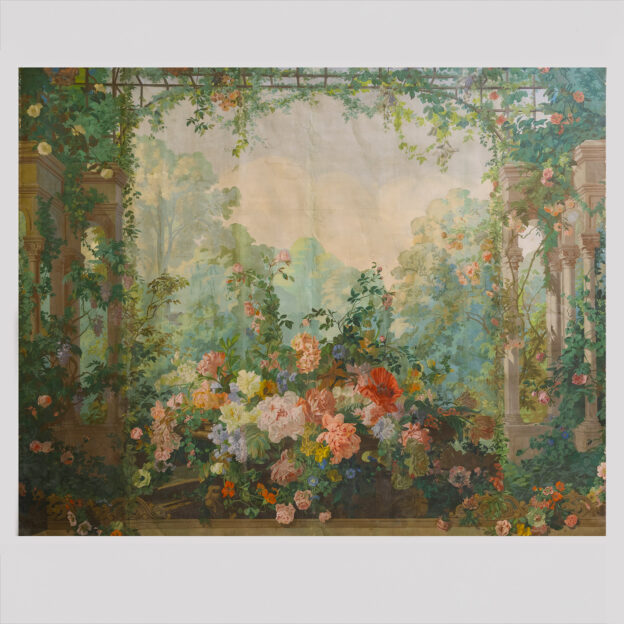

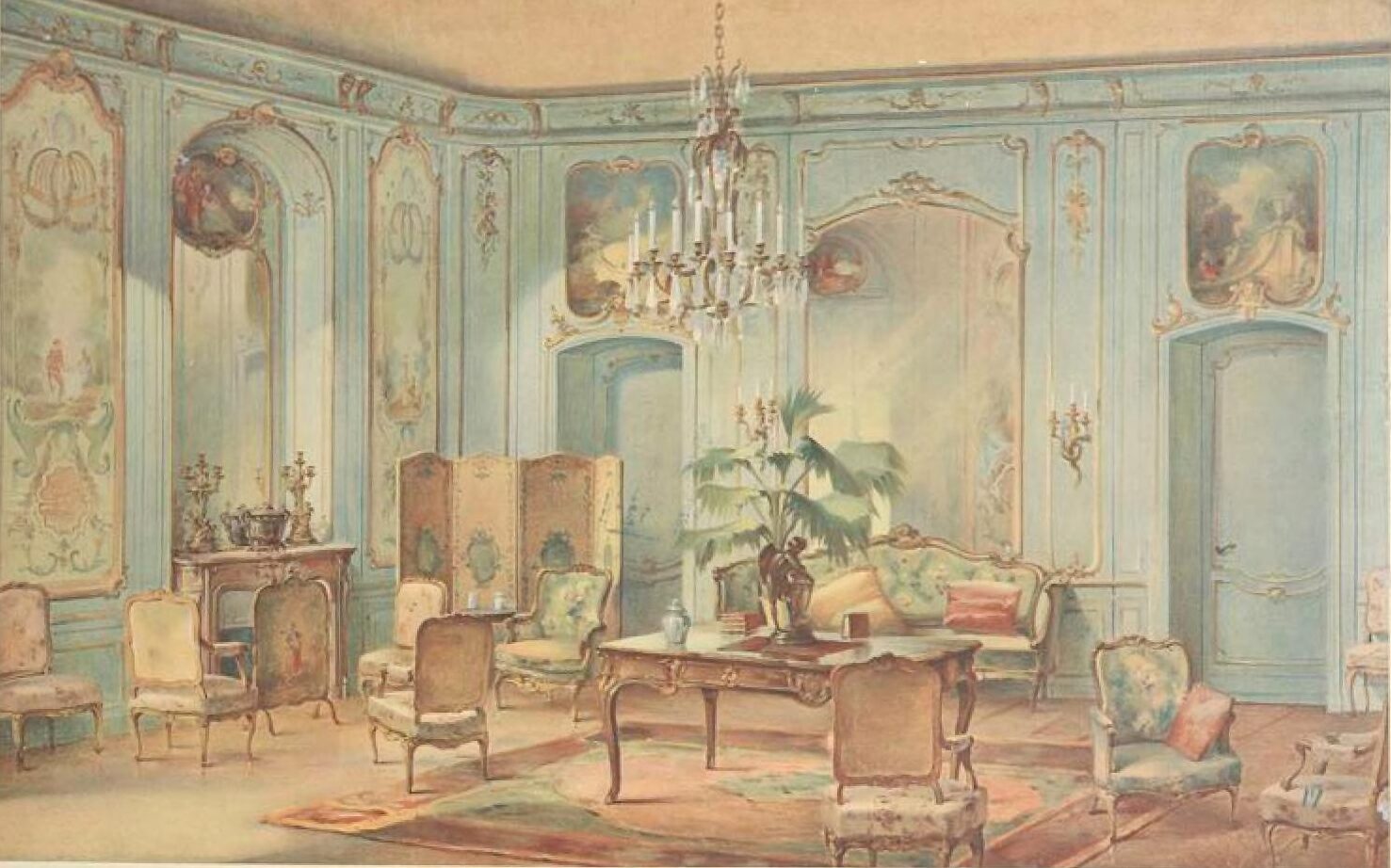

Before 1889 French furniture design indulged in a cult of the past. Meaning ébénistes devoted their considerable skills to producing ever finer replicas of famous French furniture from the Ancien Régime. Most popular where pieces known to have belonged to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. During this late 19th century revival, the skill of Parisian cabinetmakers arguably reached a technical excellence superior to their 18th century forebearers.

Watercolour of a drawing room by Georges Remon, Interieurs de style, Paris, 1907.

This fashion was not merely an emulation or nostalgia, but also a legitimate art historical exercise in recreating the glorious achievements of the Grand Siècle and recovering what had been lost during the French revolution. After all, the revolutionary sales which include a month-long auction of the contents of Versailles, had dispersed many treasures from the French royal collection across Europe. Exhibitions such as the Musée retrospective from 1865 and the Expositon de Marie-Antoinette et son temps in 1892 presented celebrated pieces from the Mobilier National for the first time to a mass audience, and they were hungrily observed by collectors and aspiring ébénistes alike. The finest cabinetmakers, especially the Beurdeley family, were replicators par excellence but also created new designs for contemporary furniture imbued with accents Les Louis.

“In France, the cabinet maker has ever excelled in the production of ornamental furniture; and by constant reference to older specimens in the Museums and Palaces of his country, he is far better acquainted with what may be called the traditions of his craft than his English brother. To him the styles of Francois Premier, of Henri Deux, and the “three Louis” are classic, and in the beautiful chasing and finishing of the mounts with which the French bronzier ornaments the best meubles de luxe, it is almost impossible to surpass his best efforts, provided the requisite price be paid; but these amounts are, in many cases, so considerable as hardly to be credible to those who have but little knowledge of the subject. As a simple instance, the “copy” of the ‘Bureau du Louvre’ in the Hertford House collection, cost the late Sir Richard Wallace a sum of £4,000.”

Frederick Litchfield, Illustrated History of Furniture: From the Earliest to the Present Time, London, 1899, p. 247

‘Le Bureau Du Roi’ – A Magnificent Exhibition Secrétaire à Cylindre

After The Model Supplied to Louis XV by Jean-François Oeben and Jean-Henri Riesener

By Emmanuel-Alfred Beurdeley, Paris, circa 1890.

This spectacular writing desk was made in circa 1890 by Beurdeley. It is superb replica of Le Bureau du Roi which was made in 1760 for King Louis XV by the Royal cabinetmakers Oeben and Riesener. It represents the very pinnacle in the art of furniture making achieved by the Parisian ébénistes of the Belle Époque . Beurdeley received awards for his submissions to the Paris exhibitions of 1878 and 1889 and at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. It is likely that this Bureau de Roi by Beurdeley was sold at the Chicogo World’s Fair of 1893 and it thereafter belonged to the ‘Robber Baron’ George Jay Gould. Art dealers such as the Duveen Brothers, architects such as Stanford White and decorators like Jules Allard, all sourced for the clients from the Parisien ébénistes, and luxury furniture and opulent decorations by Beurdeley and his contemporaries Henry Dasson and Paul Sormani, graced the Fifth Avenue townhouses and Newport Mansions of the Gilded Age.

Beurdeley’s stand at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

“These beautiful articles of furniture cannot be strictly called copies; they are elegant adaptations, which the Cressents, the Oebens, the Benemans, the Carlins, the Dautriches, and other great cabinet-makers of the eighteenth century would not have been unwilling to own.”

Henry Havard writing in the Art Journal reviewing the 1889 Paris Exposition universelle (‘The Paris Exhibition, Chapter IV. The Furniture Section’. The Art Journal, London, 1889, p. 20).

A defining characteristic of the art of the Belle Epoque is the triumph of the craftsman. The popular perception is that the craftsman was replaced by the machine, but in the art journals of the day the artist as individual is important as ever. During the Belle Époque, the reach and consumption of the decorative arts and design became truly global through the international exhibitions, trade, and the opening of new markets.

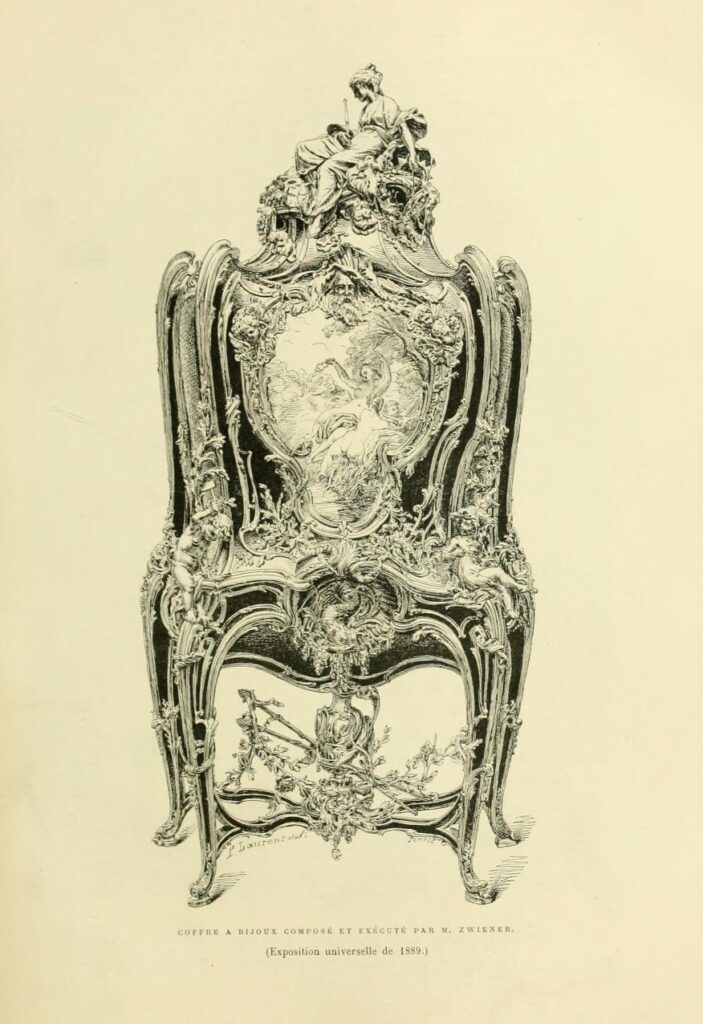

Illustrated to the right is a remarkable jewel cabinet shown by Emmanuel Zwiener at the Exposition universelle in Paris in 1889; it is exemplary of the new style evident in Belle Époque art furniture. The design by the sculptor Leon Messagé shows strong Louis XV and rococo influences and heralds the Art Nouveau style. It was bought from the Paris exhibition for Maria Feodorovna, Empress of Russia (1847-1928).

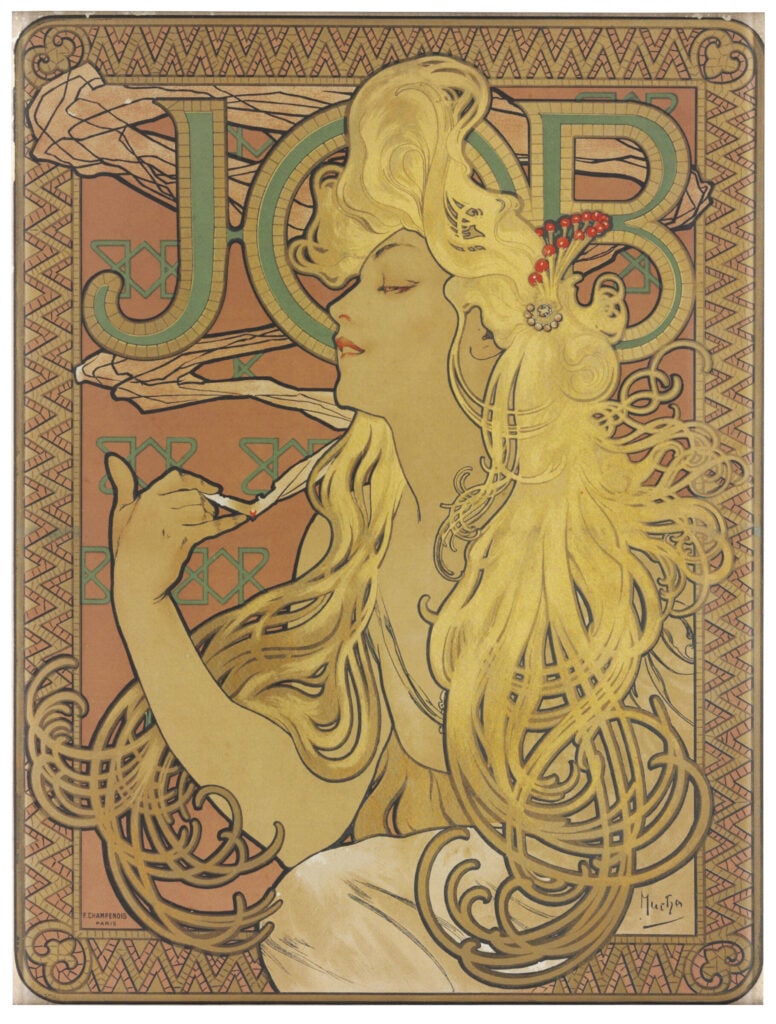

Alphonse Mucha’s poster for Job cigarette papers is one of the most famous works in design history and provides a vision of Belle Époque Paris. The fine-art advertising poster was a creation of the Belle Époque when mass production created global brands and mass marketing. It was the dawn of advertising’s golden age. Advances in print making and advertising poster production made artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec household names, beginning a period of mass, almost disposable, art

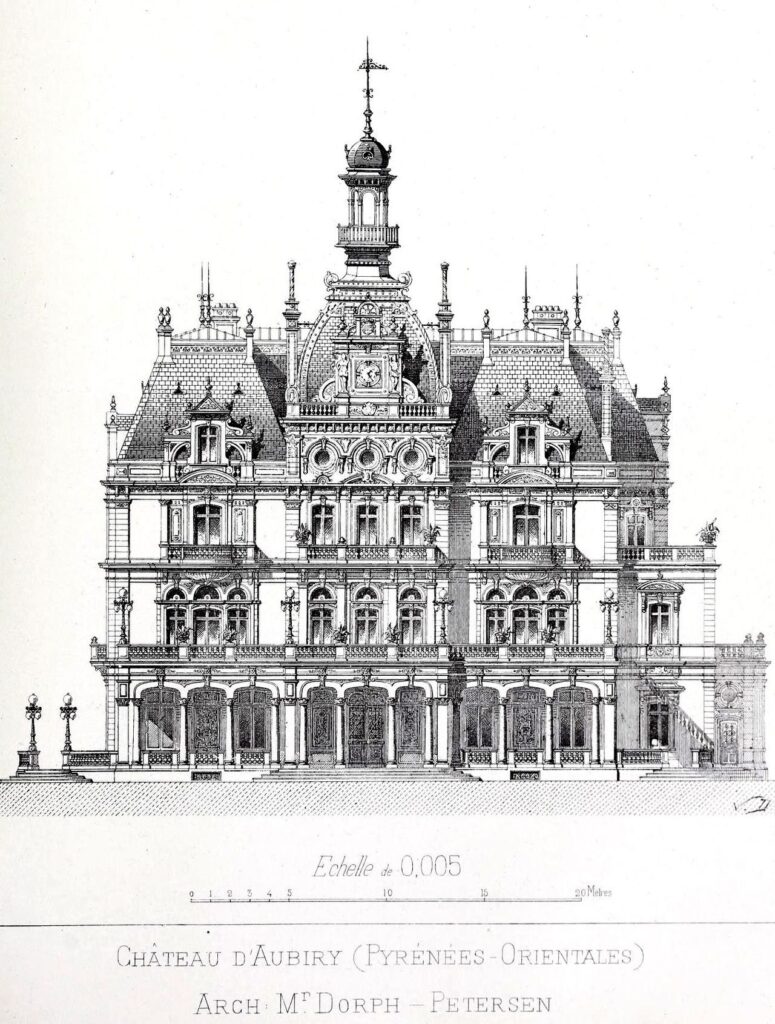

One of the inspirations for Disney’s Cinderella Castle, the magnificent Belle Époque château d’Aubiry located in Céret, Pyrénées-Orientales, was built between 1893 and 1904 for Justin Bardou, principal heir to the Job cigarette paper manufacturers of Perpignan, France.

L’exposition de sculpture at the Grand Palais for the 1900 Exposition universelle.

The number of works of art exhibited was astounding, with 3,066 for the Centennale, 3,336 for the Décennale and 4,967 for all the foreign sections. The press encouraged visitors to return several times so as not to be overwhelmed. The Palais des Beaux-Arts exhibition also provoked admiration.

“A more magnificent assembly of beautiful things is unimaginable!”

Of the decorative arts shown at the 1900 Paris Exhibition, and in the history of furniture, no piece better exemplifies the triumphant ambitions of the French Republic as it embarked into the new century than this bookcase with sculptural figures. Breathtaking in scale and conception ‘La Grande Bibliothèque’ was the chef d’oeuvre of its maker François Linke, whose stand at the 1900 exhibition was awarded the gold medal establishing him as the most famous ébéniste of the Belle Époque.

“Mr. Linke, since 1900, has had the satisfaction of being awarded first place for his pieces of grandiose richness and composition which have won universal admiration, here shows a collection of furniture of great beauty.”

(Report for the Exposition universelle et internationale de Liège, 1905)

There came about towards the end of the century a new artistic style, the formation of which was greatly hastened by the promotion of French art for the 1900 exhibition. This new style was characterised by sinuous lines and organic forms and had its origins in Japonisme and Aestheticism. It was also the strongest rebellion yet against the historicist and revival styles which dominated, and for this reason, was coined Art Nouveau.

The Belle Époque interior of the restaurant at the Langham Hotel, Paris, later known as La Fermette Marbeuf and the ‘Salle 1900’, was opened as part of extensions to the hotel to welcome visitors to the 1900 Paris Exposition universelle. A masterpiece of the Art Nouveau it was created by architect Émile Hurtré, the craft painters Hubert and Martineau and the ceramicist Jules Wielhorski. It was boarded up before the Nazi occupation during World War II and only uncovered in the 1970s by an unsuspecting café owner who had bought the adjoining rooms.

Organic carving to a stair banister and handrail at the Villa Majorelle is characteristic of Art Nouveau.

Central to the Art Nouveau movement was a group of artists and artisans located in and around the city of Nancy in northeast France. Their work was inspired by the floral and naturalistic forms found in the Lorraine region and centred about the glass manufactory of Daum. Collectively their style is referred to as the École de Nancy. Major figures included the glass designer Jacques Grüber (1870–1936), the furniture maker Louis Majorelle (1859–1926) and glass and furniture designer Émile Gallé (1846-1904). The group participated with great success at the Exposition universelle of 1900 and at the Exposition Internationale de l’Est de la France which was held in Nancy in 1909.

The American actress and dancer Loïe Fuller (1862-1928) was the embodiment of the Art Nouveau movement. An artistic sensation she combined her choreography with silk costumes illuminated by multi-coloured lighting of her own design, creating the ‘Serpentine Dance’ which inspired artists including Auguste Rodin, Toulouse-Lautrec and notable sculptural depictions by Raoul Larche.

Loïe Fuller photographed by Frederick Glasier, 1902

The achievements of the French artists, artisans, architects, and craftsmen, as exemplified by the Paris 1900 exhibition, represent a golden age of artistic endeavour. These achievements belonged to the parents of the lost generation of the First World War, and their dreams and aspirations died with their children. The essence of the Belle Époque is the memory of beauty and magnificence, and for the student of design history it is the highpoint of craftsmanship as best represented by the opulence and finesse of furniture produced at this time. Following the First World War, there were shortages of materials and too few apprentices to train in the applied arts. Moreover, there was a collective sadness in looking back at the art of La Belle Époque, it all seemed so full of false promise. For these reasons, the Belle Époque continues to conjure in the popular consciousness images of a halcyon age.